reflections from our summer writing fellows

Dear Insurrect! readers,

This fall, we are excited to publish multiple articles by our two summer writing fellows, Alejandra Marquez and Thai-Catherine Matthews. As part of this series, we’d like to share their reflections on writing for Insurrect! as graduate students and humanities scholars invested in anti-colonial research methods. Please take a moment to read through their thoughts below.

And also check out our archive for their most recent publications:

“Injustice and Romance: Critical Reflection on Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona” by Alejandra Marquez

“Taking One’s Place: Affirmative Action and the Legacy of Academia’s Black Expats” by Thai-Catherine Matthews

Alejandra Marquez | Insurrect! Post-Summer Reflection

Opportunities to share your research interest and have a space to create a conversation on these topics are few and far between. As a graduate student and an academic, there are expectations that you should be writing and publishing consistently. Yet, no one talks about the small amount of opportunities there are for publication, the fear of rejection, or the mystery that is the publication process.

It is even more rare to find an opportunity that so closely aligns with your interest as a scholar and is open to your interest and not a limited range of topics. Writing with Insurrect! has been an eye-opening experience for several reasons but mostly because of the commitment to allowing writers to deep dive into topics that are important to them. To be able to explore the way that archival practices have been influenced by colonialism, can be a bit of a taboo subject given that it is such an institutionalized ideology and practice. Reimaging a community-based approach to archival practices and thinking about how to best implement these practices is a task of its own, but to be able to research and write about this topic for a publication patron that models the reimaged approaches you discuss is a unique experience.

In my exploration of finding alternatives to traditional archival practices, I found resources that focused on community-based archival practices which places community creators at the forefront and leaves the decision-making process with the members of the community whom the archive is meant to serve and represent.

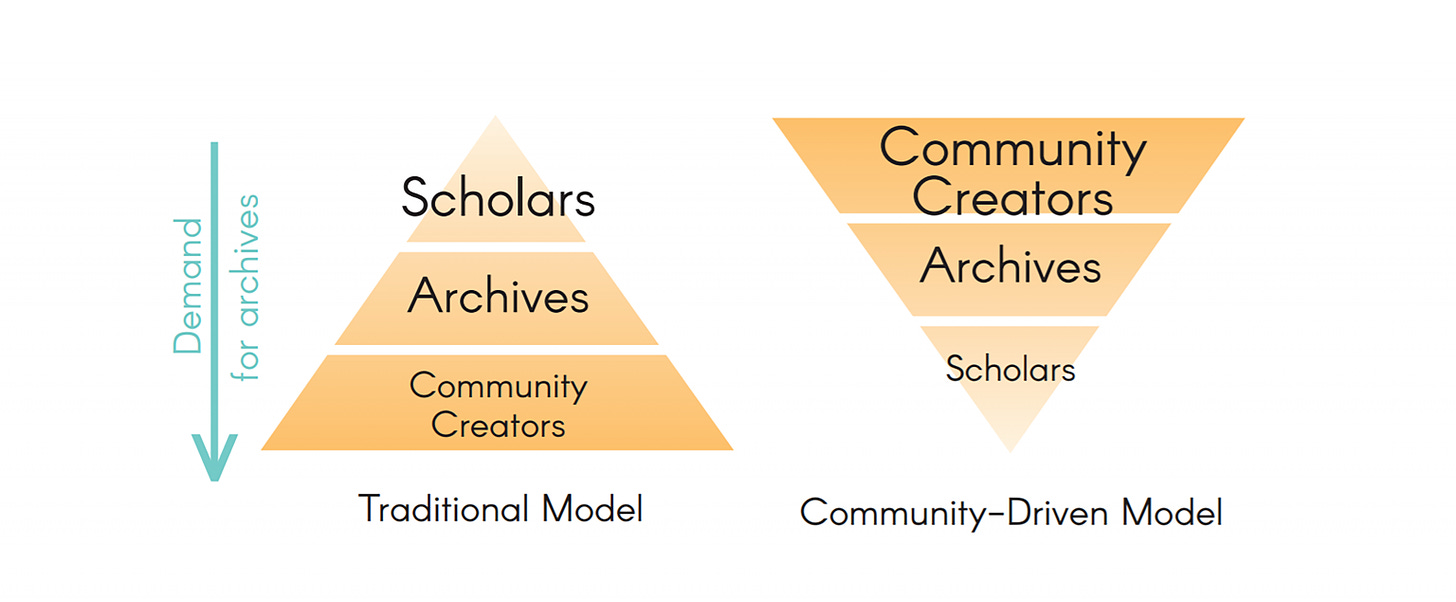

The article “What is a Community Archive?” posted by UNC Libraries provides the diagram above, which compares the traditional model of archival practice which prioritizes scholars and institutional interest over the needs of the community or the public who are meant to be able to access the archive. The traditional model of archival practices has historically had a Euro-centric approach that sets a select group of academics to determine what is considered relevant or important enough to be archived. In doing this, it negates the needs of the community and the public who may have a better idea of what materials should be archived, especially in instances of archives representing marginalized BIPOC communities. Traditional models of archival practices also have more limitations on what constitutes as an object or material that can be archived. In traditional archives, there is a focus on physical materials (books, prints, and objects) rather than materials like oral histories.

Through the community-based community, the needs of the community are at the forefront and reflect a more accurate understanding of what objects and materials are a truer representation of the community as a whole. As the diagram reflects, community creators can work together with scholars to maintain the archive while keeping the needs of the community as the priority. Leaving the agency of the archive with the community serves as a decolonial action to the traditional Euro-centric model of archiving that has been prevalent for so long.

By putting writers at the forefront of their archive, Insurrect! models the community-based approach to archival practices which moves away from the Euro-centric traditional approach. In doing so it serves as an anti-colonial space that challenges the deeply rooted colonial ideologies embedded in archival practices.

Thai-Catherine Matthews | Insurrect! Post-Summer Reflection

Living in my skin means living in the past, as equally vulnerable to the ever-present racial violence that stalked my ancestors, defined by estrangement from a country and culture these same ancestors built. Between now and history is an entire conversation I’d never been comfortable having with my predominantly White friends at my predominantly White institutions, experiences I could only try and repeatedly fail to articulate as the financial-aid student at every rich and ritzy, suede-dipped and shiny, opportunity I knew I was somehow lucky to have despite having earned my place through hard work and high grades and never—ever—forgetting how much debt my single-mother was accruing, how desperately my disabled grandmother was saving, and any odd jobs I could pick up between chores and homework. Living in this place between what was and what I fear always will be meant, for as long as I could remember, learning how to cope with heartbreak and horror.

I’d written about racial inequity before joining Insurrect! as a Summer Writing Fellow: poems, short-stories, unpublished op-eds. I’d grieved, I’d raged, I’d admitted to my husband how genuinely afraid I was to have sons in a world where his White privilege could never protect them. This desire to do something more than hurt challenged my faith in academia: how could my classroom skillsets—research, writing, analysis—ever presume to confront evils as foundational as racism? Could the words I’d always believed in ever be enough?

My time with Insurrect! this summer has meant reevaluating my aims and aspirations as an academic. It’s meant learning how this work can be more public-facing, more public-serving. It’s meant relief for me, in many ways, understanding that doing the work of history helps us live its its aftermath, occupying ‘the between’ now and the past with something like integrity and dignity as we write our way forwards into conversations we hope will positively impact the future.

This summer was big for US history in particular. While history as a concept has always been political, we live now in a moment that sees its implementation as a curriculum deliberately besieged. Paradoxically, it is at the moment of its attempted dismantling that History reveals its real and relevant importance: it’s no accident that men who want to control the future of this nation’s voting public are attempting to erase any knowledge of the past. In going back to facts we being to understand racism, sexism, homophobia and xenophobia are more than concepts; they are living, breathing, monsters born on specific dates at nameable places–implemented by specific people who either acted or looked away, who legislated or participated…or benefitted.

I close this summer strangely heartened by the horror of what we see unfolding in Florida’s flagrant attempt to undermine the classroom and strip education of the power to unite the next generation in opposition to harmful, systemic, hierarchies. Where Humanities curriculums have struggled to articulate why they are needful, History now proves its importance through its very persecution. What if History could demonstrate that the overwhelming economic inequity amongst people of color in the US can be directly traced to the historical legislations barring them from gaining equity through homeownership, or mass-executing successful entrepreneurs, or thwarting Black-founded settlements because Black prosperity threatened to make these populations a political force?

Would the historic records destabilize contemporary stereotypes?

Would teaching students to make these connections change the way they voted? Could it Deepen what they demanded of their thought-leaders?

To me, what Insurrect! represents is an academia that aims for activism: a belief in the power of words and research to change lives by relying on unchanging facts. It represents a way forward, fueled by a closer look at the past. For me, living between now and history has always meant assuming a position of defense: but I’m also beginning to think that this position can be a stance of resistance as well, one that puts my own work to work for the purposes of building a better world.

Further Reading:

Antonio Planas, “New Florida standards teach students that some Black people benefited from slavery because it taught useful skills,” July 20, 2023.

Jaclyn Diaz, “Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signs a bill banning DEI initiatives in public colleges,” May 15, 2023. National Public Radio.

“The humanities belong to everyone,” The National Endowment for Humanities, Dec. 11, 2013.